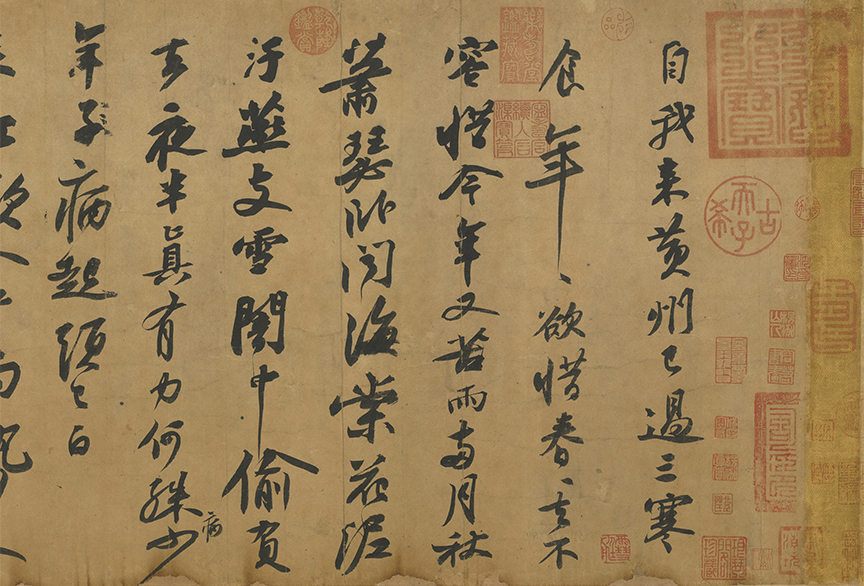

The Cold Food Observance manuscript was composed in 1079 while Su Shi was living in exile in Huangzhou (Huanggang, Hubei). On the Cold Food Festival in the fourth month of his third year there, he was inspired by the change in seasons to comment on the difficulties of life and the frustrations in his official career, composing "Two Poems on the Cold Food Observance in Rain," which he later transcribed in calligraphy to this hand scroll. Later generations praise this manuscript as Su Shi's best surviving calligraphy. At the end of the manuscript is a colophon by Huang Tingjian, adding another layer for appreciation.

This film utilizes the newest animation technologies to capture the dramatic interplay between the fluctuating emotions in Su Shi's poems and the expressive ink traces left by his brush. Su Shi's characters lean here and there in a bold and unrestrained manner, exhibiting complexity in rhythm and form.