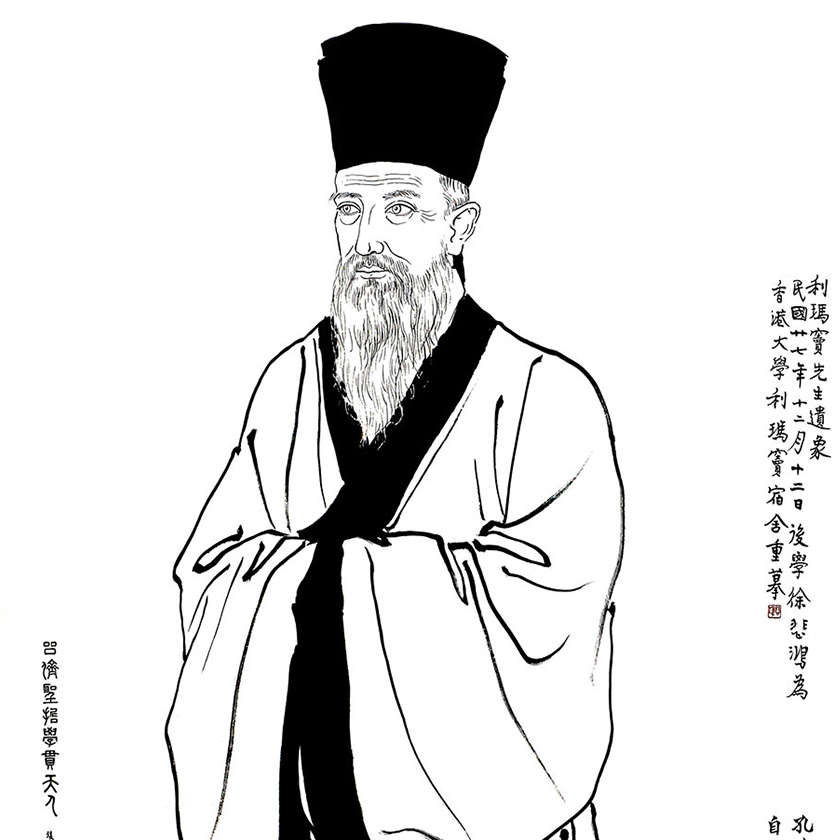

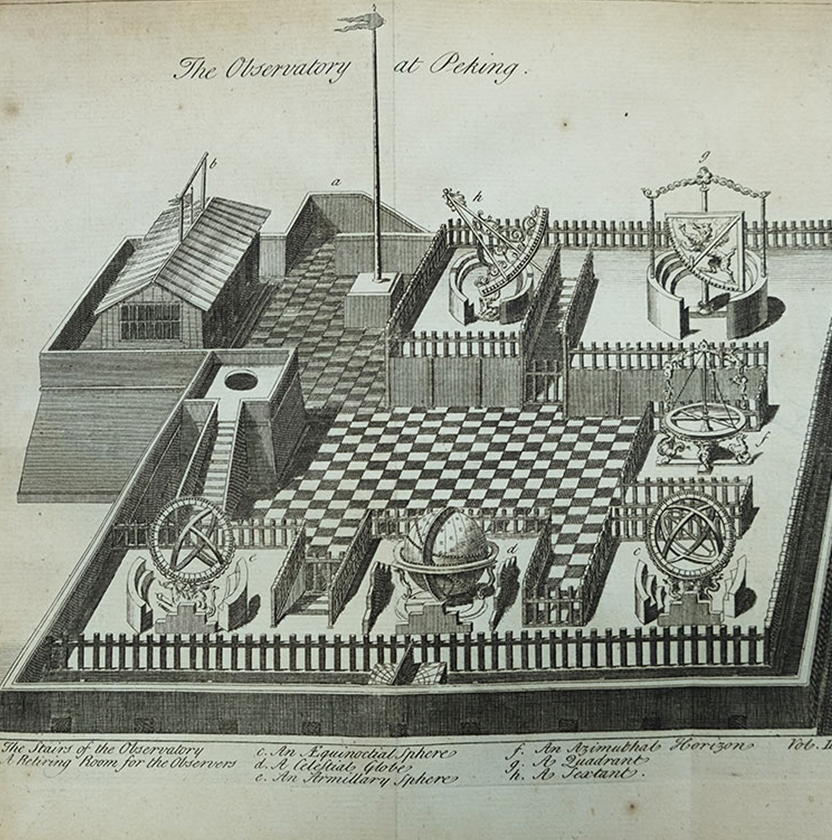

This accompanying exhibition enables visitors to understand the intellectual and cultural context within which Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang-Shining) produced his highly influential artwork. Through prints, early books, porcelain, and paintings, viewers can see the significant role played by Jesuit missionaries, such as Castiglione, in the late Ming and Qing dynasties. Invited by the emperors, Castiglione and other Jesuits put their scientific and artistic skills to work for the imperial court. Their presence both inside and outside of the Beijing court initiated the first sharing of Eastern and Western philosophical and scientific knowledge as well as the development of new artistic practices. While the Jesuits introduced European artistic naturalism and perspective to the Chinese court artists, they in turn exposed the Jesuits to new artistic technologies such as silk-making and porcelain. The exhibition demonstrates this ongoing exchange in Chinese porcelains made for European export with European forms and scenes; in translations of seminal texts into each other's languages (Euclid and Confucius shown here); in the production of the first topographic map of a country; and of course in Castiglione's famous paintings, which blend European naturalism and Chinese landscape aesthetic. The exhibition concludes with the 1938 "Portrait of Matteo Ricci," attributed to Xu Beihong, testifying to the significance of the Jesuit influence through the twentieth century.

Curator:Dr. Isabelle Frank

- The University of Hong Kong Museum and Art Gallery

- The University of Hong Kong Libraries

- Hong Kong University of Technology and Science

- Chinese University of Hong Kong

- Hong Kong Maritime Museum

![A Sketch of the Hollows or Sites of the [Heart] Beats](../common/images/selection/img5_3s.jpg)