The largest number of painting and calligraphy artworks that the Qianlong emperor appreciated during his southern inspection tours is found in the collection of the National Palace Museum. Some of the works he took are arranged chronologically here according to the six tours. In addition, they are presented on the basis of the route to show his method of appreciating art related to local artists, scenery, and historical events of the places he visited, which he also commented on. Qianlong's appreciation of particular works he often brought along appear in his repeated inscriptions on them or those of similar themes, testifying to his unique habit of frequently writing on an artwork over different periods of time.

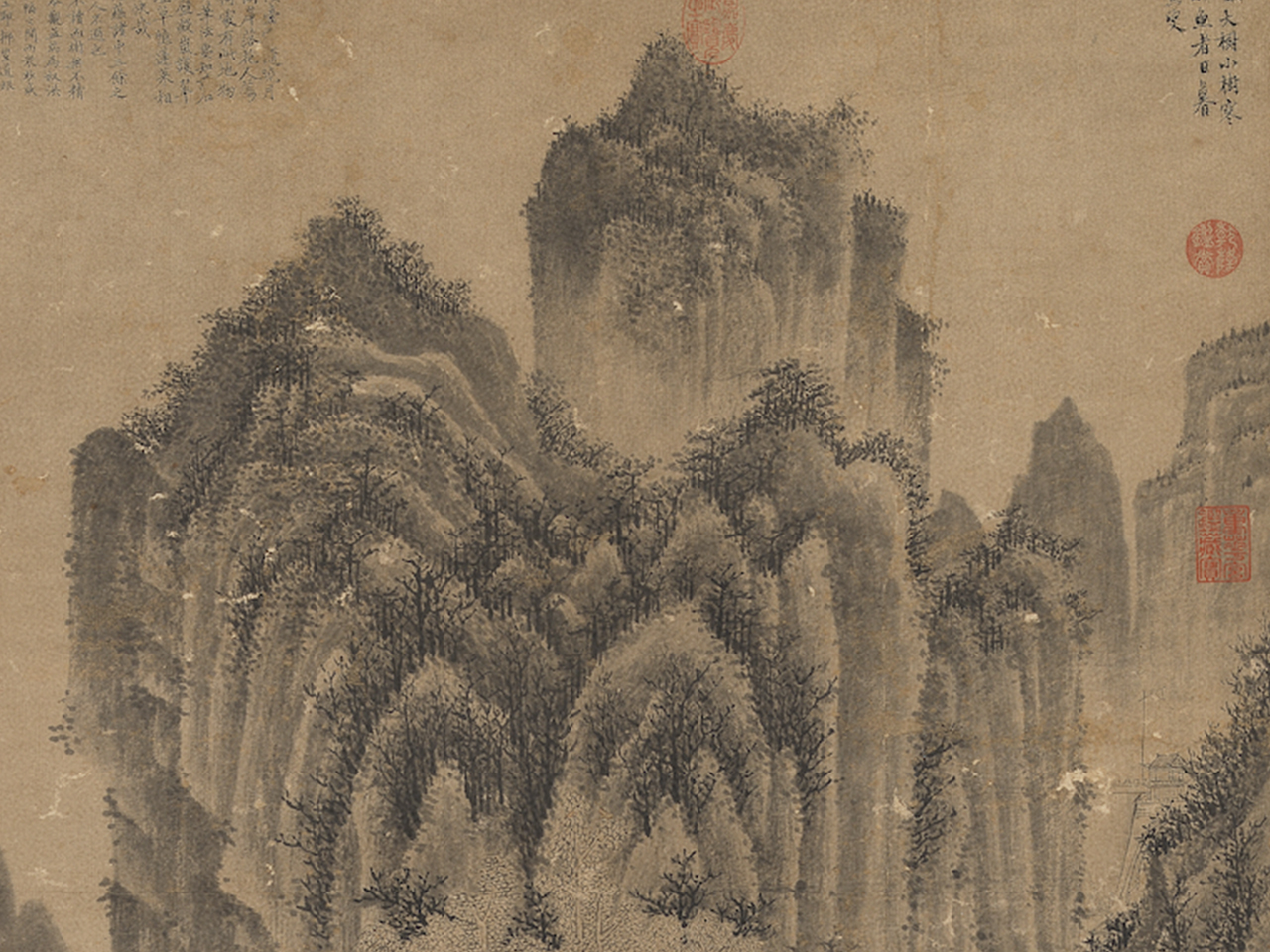

Landscape in Monochrome Ink

- Wang Fu (1362-1416), Ming dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 157 x 67.2 cm

Wang Fu was a Ming dynasty artist whose works caught the eye of the Qianlong emperor. A native of Wuxi who went by the sobriquets Jiulong shanren and Aosou, Wang was most renowned for his bamboo painting in monochrome ink. In landscapes, he followed the style of Yuan dynasty literati artists, being a vanguard of the Wu School of scholar painting that emerged later in the Ming dynasty. This work features dense layers of crags and forests. Of the fishing boats in the foreground, on one a stove is being prepared and in another a meal is taking place, with clothes being put out to dry as well. In the middleground a boat has folded its sail; travelers to the right on a mountain path quickly make their way to a city gate, indicating the time of day as dusk.

When the Qianlong emperor appreciated this painting on his southern inspection tour, he did not just thoughtlessly take it out to appreciate the landscape. Rather, he paid special attention to the details of daily life among commoners on the boats, which form the focus of his inscription. As such, it demonstrates Qianlong's eye for detail and attention to the life of people when examining paintings.

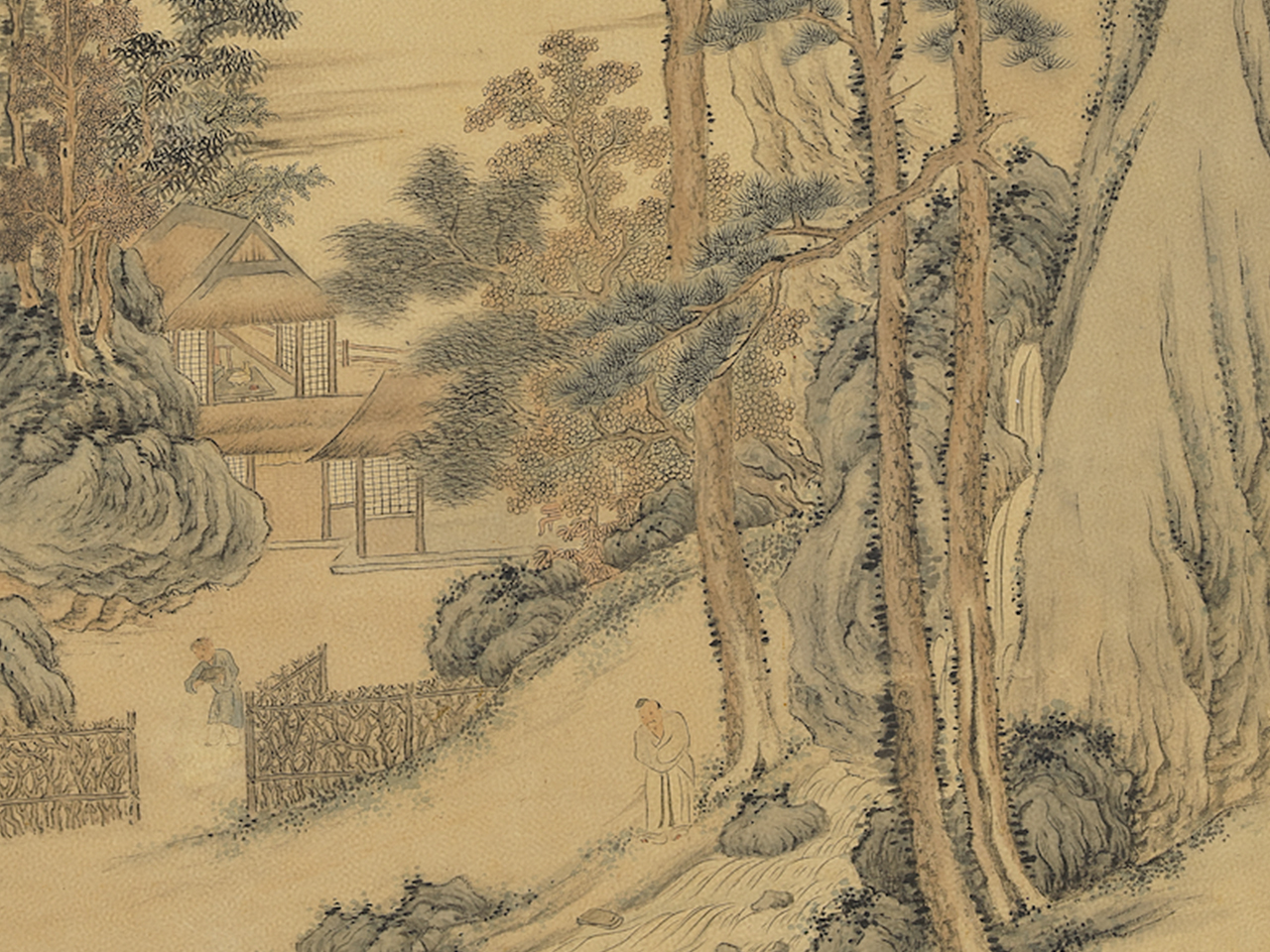

Washing the Inkstone

- Chen Guan (1563-ca. 1639), Ming dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and light colors on paper, 122.4 x 51.5 cm

This painting was done by Chen Guan, an artist in the school of Wen Zhengming active in Suzhou, at the invitation of his friend, Lu Zichui, who was fond of collecting ancient inkstones. In his poetry inscribed on the work, the Qianlong emperor wrote, "The clay inkstone is washed thrice and venerated thrice. I roll my sleeves by the flowing waters and gaze at the clouds of ink." He perhaps is describing this interesting scene in the painting of a scholar looking at an inkstone half submerged in the waters by the riverbank.

The date for the poetry inscribed by the Qianlong emperor in the upper right of this scroll is a "spring day in the 'renwu' year," which differs from the intercalary fifth month after Qianlong's return from his third southern inspection tour as recorded in Third Anthology of Imperial Poetry. Perhaps an editing error occurred in the compilation of the text. It is, however, not the only example of a discrepancy between the date of the emperor's poem inscribed on a painting taken on a southern tour and that recorded in his compilation of poetry.

Stepping in Snow on a Plank Bridge

- Attributed to Ma Yuan (fl. ca. 1190-1224), Song dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and light colors on silk, 99 x 59.1 cm

The Qianlong emperor took this work on his sixth southern inspection tour. His inscription of poetry dated to the "jiachen" year probably was written in the Yangzhou area on the way back to the capital in the third intercalary month of that year, 1784. The last two lines of his poetry, "The inscriber was gifted at painting and at poetry, among the Mongols he was a gem unparalleled," refer to the author of the poetry in the upper right, Boyan Buhua. He is also the artist of "Clouds and Pines in an Ancient Valley," which the Qianlong emperor had inscribed ten days earlier and was referring to here.

The signature for "Ma Yuan of Hezhong" that appears in the lower left corner is a later addition. Judging from the rock formations, outlines of the figures, sharp drapery lines, and angled tree branches, the painting probably came from the hand of the Ming dynasty artist Ma Shi (fl. early to middle fifteenth century). It nonetheless conveys the stylistic features of Ma Yuan's painting, which is no wonder why Qianlong considered it to be a fine work of his.

Su Shi Forfeiting His Belt

- Cui Zizhong (?-1644), Ming dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, 79.4 x 50 cm

Cui Zizhong, style name Daomu, was a famous "transformational" painter of the late Ming dynasty. The forms in this hanging scroll, such as the rocks, trees, and plum branches, are therefore rendered in an angular manner for an eccentric touch. This work illustrates the story of how the Buddhist monk Foyin engaged in a poetry contest with his friend Su Shi, the famous Northern Song literary great and official, at Jinshan Temple. After losing, Su forfeited the jade belt he was wearing. In the painting, Su is shown holding a blue belt-like object, the artist probably referring to Su's belt adorned with pieces of jade.

While the Qianlong emperor was on his third southern inspection tour in 1762, he suddenly remembered this painting by Cui Zhizhong stored in the imperial study. As he recounts in the inscription, he ordered that it be sent by special delivery to Jiangnan for his appreciation. Later, this painting would become a frequent companion on the emperor's southern tours, being taken out each time he stopped at Jinshan Temple to recall the story of Su Shi forfeiting his jade belt.

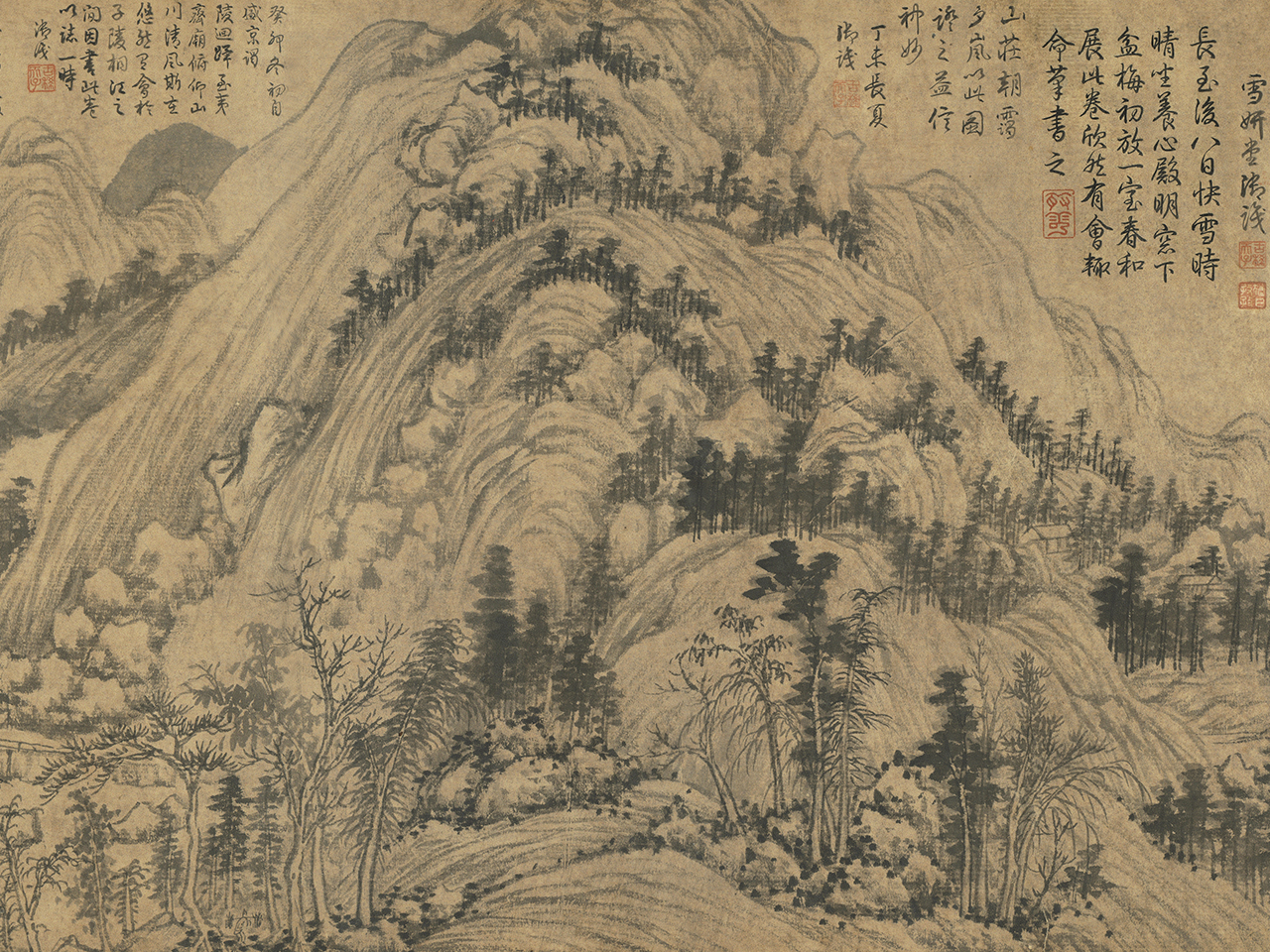

Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains

- Attributed to Huang Gongwang (1269-1354), Yuan dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 32.9 x 589.2 cm

The Qianlong emperor considered this "Recluse Ziming" version of "Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains" to be the authentic one by Huang Gongwang. From around the time of Qianlong's first southern inspection tour in 1751, he often took this work in his luggage, bringing it out to leave an inscription of praise when he came across a particularly scenic site. The southern tours were no exception. In his 1784 inscription on this painting, he wrote, "On the six southern tours, the scenery of mountains and rivers I experienced was majestic and grand. At the time I took out this handscroll to corroborate it, (the scenery) matched in every way." Except for the fifth southern tour, when Qianlong did not write on the work, he left behind inscriptions on scenery at Shaoxing, Hangzhou, Mount Lingyan, and Mount Qixia.

Of all the works in the imperial collection, the "Ziming" version of "Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains" was one of the dearest travel companions of the Qianlong emperor throughout his life.