In the twelfth lunar month of the eighth year in the Zhiyuan reign (1271), Kublai Khan changed the name of his country from "Ikh Mongol Uls (Great Mongolian Nation)" to the "Great Yuan," becoming the first emperor of the Yuan dynasty. Afterwards, the Yuan would go on to conquer the Southern Song and control Mongolia south of the Gobi. Taking the lands originally occupied by the Jin dynasty and Western Xia, the Mongol Empire came to incorporate a unique entity known as the Mongol Yuan. Not until the eighth month of 1368, when Ming dynasty troops entered the Yuan capital of Dadu and Emperor Shundi fled north, did the "Yuan dynasty" in Chinese history come to a close.

During this period, a large number of artisans came to the Yuan court from various places in Central Asia. Various cultures commingled, the pluralism resulting from their interaction manifested in the forms of art produced at the time. This section of the exhibit takes a look at the art of the Chinese scholar Zhao Mengfu and his wife, Guan Daosheng, as well as the artistic heritage of their son, Zhao Yong, also touching on efforts in traditional painting by such reclusive artists as Wu Zhen and Ni Zan. Just as important, it examines new aspects in painting and calligraphy introduced by such artists of non-Chinese background as Gao Kegong and Guan Yunshi.

In terms of religion, Tibetan Buddhism flourished in the Yuan dynasty under the patronage of the Mongols. "Thangka of the Taklung Monastery Abbot Tashi Pal," for example, is representative of the Tibetan style of painting at that time. New combinations of elements are also seen in textiles of the period, such as "Image for the New Year," which had been previously attributed to the Song dynasty. And though the textile of "Ratnasaṃbhava" may date later than the Yuan dynasty, its motifs point to cultural exchange in the Mongol Yuan period continuing into the early Ming dynasty. These and other works reveal the new and unique forms of cultural diversity in the Mongol Yuan era.

Kublai Khan Hunting

Rotation 1 10/6-11/15

- Liu Guandao (fl. latter half of the 13th c.), Yuan dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 182.9 x 104.1 cm

The imperial couple is accompanied by figures in various poses. One of them bends a bow, another holds a falcon, and one has a hunting leopard. The pronounced facial features of the men indicate they belong to various ethnicities, this hunting scene amply demonstrating the idea of cultural pluralism and ethnic integration at the Yuan court. The scroll is dated by the artist, Liu Guandao, to 1280, a year after he had been rewarded for painting with a post in the Imperial Wardrobe Service.

Bust Portrait of the Yuan Emperor Wenzong

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Album leaf, ink and colors on silk, 59.2 x 47 cm

This portrait of Wenzong was remounted much later by the Qing dynasty court. On the left is an inscription in three characters for "Jiyatu" using the new phonetic system for Mongolian devised in the Qianlong reign during the eighteenth century. The leaf was calligraphed in approximately 1815.

Bust Portraits of Yuan Dynasty Imperial Consorts

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Album leaf, ink and colors on silk, 61.2x47.7cm

One of the most famous portraits in the album, that of Kublai Khan's consort, Chabi, is currently on overseas loan in the United States for exhibit and not available for display. On the left side of the leaf with Chabi's portrait is the consort of Emperor Shundi (Togon Temür), the mother of Princess Sengge Ragi. The three leaves on display here include five portraits. One is of Nahan, Emperor Yingzong's (Gegeen Khan) consort, but the other four are missing the labels, so their identities are unknown. The tall decorated headwear worn by the consorts is known as a gugu crown, and the ladies are all shown wearing robes woven with gold strands.

Traveling by Horseback in a Spring Countryside

- Zhao Yong (1289-after 1360), Yuan dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 88 x 51.1 cm

This hanging scroll represents a traditional composition of a figure under a tree. The man on horseback wears a red robe and holds a bow in his left hand, on which his right hand rests. The horse has come to a stop below a large tree as he turns to look back. The stout white steed seems to have been reined in, its head bent down slightly to the side. Its right hind leg is also raised, making this a portrait of stillness and movement for both figure and animal. Zhao Yong not only learned painting in the family tradition but also pursued revivalism, the tree leaves depicted here all outlined with ink lines to which blue-and-green coloring was added, the simple quality revealing archaic notions about Tang dynasty art.

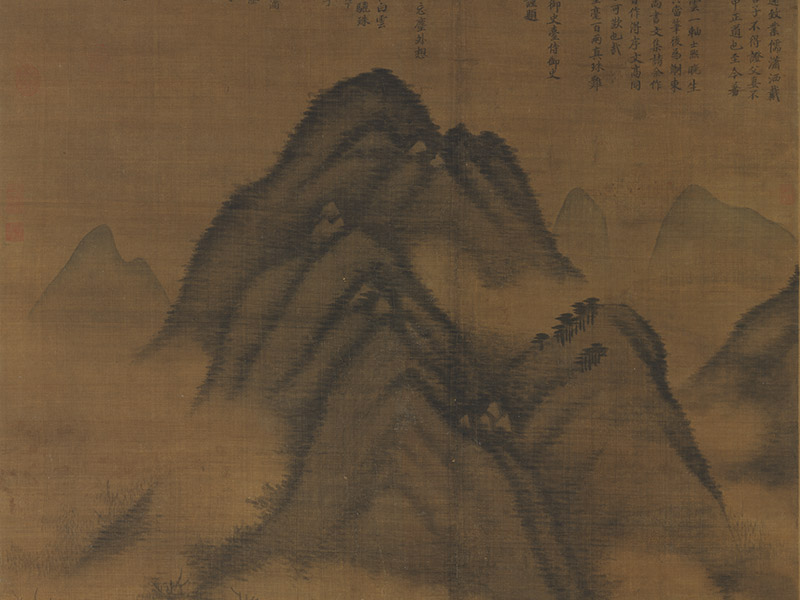

Verdant Mountains and White Clouds

- Gao Kegong (1248-1310), Yuan dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and light colors on silk, 188 x 110.5 cm

This hanging scroll reveals Gao Kegong's revivalist manner, the mountains representing a fusion of the brush methods from Northern Song monumental landscape painting with those of Dong Yuan and Juran in the Jiangnan area. The clouds enveloping the foothills in the middleground further reveal elements of landscape painting by Mi Fu and Mi Youren, the blue-and-green coloring also hinting at its distant origins in Tang dynasty landscape painting. Histories in art generally indicate that Gao Kegong studied the style of cloudy mountains practiced by the Mi Family, but he actually incorporated the solidity of Northern Song monumental painting as well, indicating an openness for classical modes of expression in Chinese art.

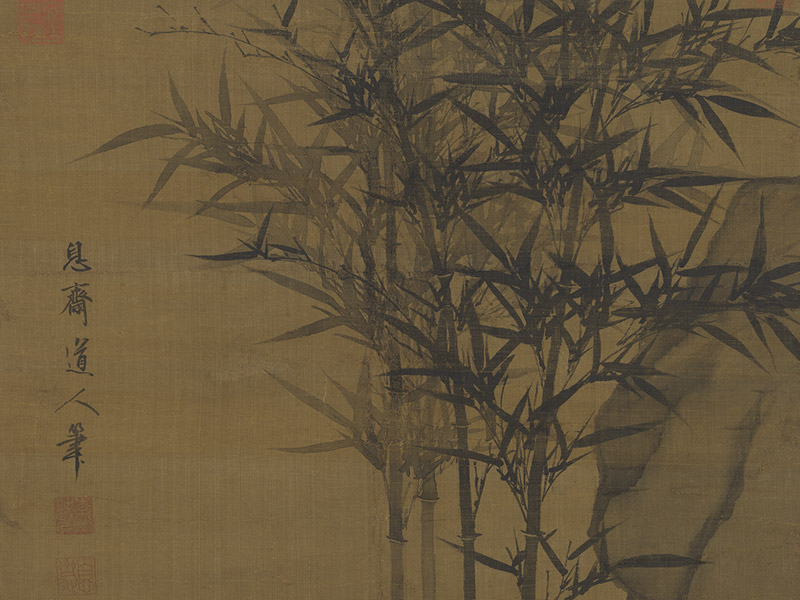

Peace Throughout the Four Seasons

- Li Kan (1245-1320), Yuan dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink on silk, 131.4 x 51.1 cm

This hanging scroll depicts four stalks of bamboo on a gentle slope, the arrangement on the ground front and back clearly indicated. The artist used shades of light and dark ink to express the spatial relationship between the leaves, which above intermingle in a dense and complex mass. The result is a beautiful and dazzling visual effect. Li Kan reportedly was also an envoy to the state of Cochin (Vietnam), where observed large tracts of bamboo, providing him with the means to surpass the ancients when it came to painting this subject.

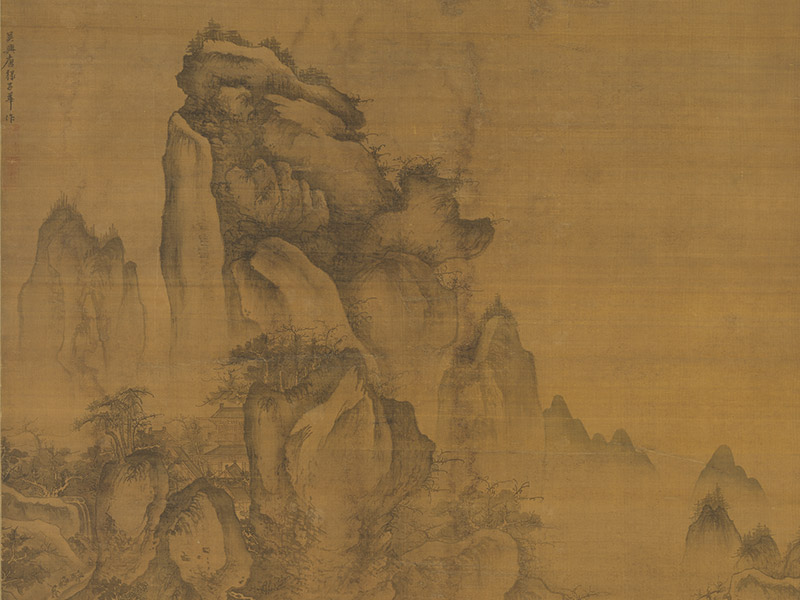

After Guo Xi's "Travelers in Autumn Mountains"

- Tang Di (1287-1355), Yuan dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and light colors on silk, 151.9 x 103.7 cm

This painting has the main mountain complex situated in the middle with peaks and valleys on either side. In the foreground are bulbous landscape forms and buildings behind, the composition bearing a likeness to that found in Guo Xi's "Early Spring" also in this exhibit, suggesting a relationship between the two in way or another. However, the brushwork and structural arrangement of the mountains here have replaced the nimble washes of ink in Guo Xi's painting with more lines, the differentiation between rock forms also more distinct. Thus, it portrays a new direction in the Li-Guo landscape tradition promoted by northern scholars at the time.

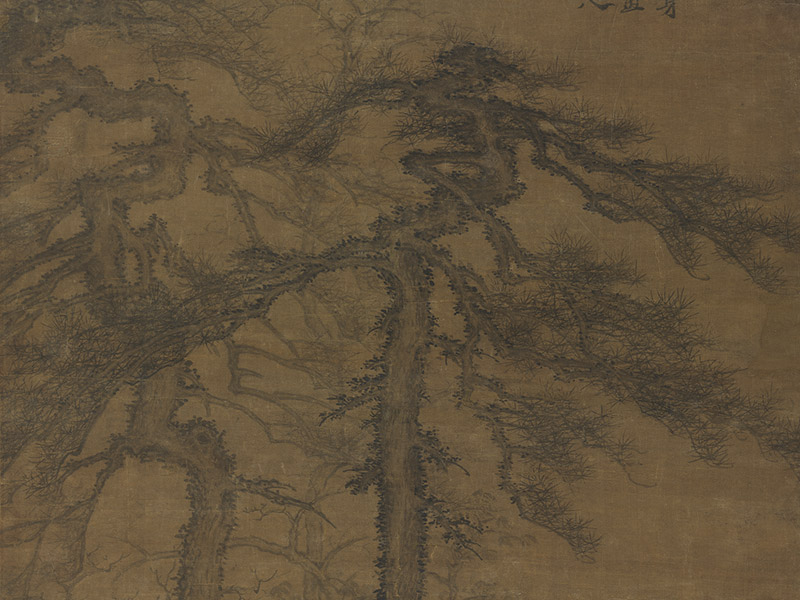

Two Pine Trees

- Cao Zhibai (1272-1355), Yuan dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink on silk, 132.1 x 57.4 cm

On the painting is an inscription by the artist that reads, "On the 'Human Day' (7th day of the 1st lunar month) in the second year of the Tianli reign (February 6, 1329), Yunxi did this screen of pine trees to be sent to Shimo Boshan as an expression of remembrance." Shimo Boshan (1281-1347) was an influential Khitan official who was the great-grandson of Shimo Yexian, a meritorious figure in the Mongol defeat of the Jin dynasty. Not long beforehand, Shimo Boshan relinquished his post at court to become Commander of Fujian. Cao Zhibai probably used the imagery of two stalwart pines reaching to the skies to praise the virtue and uprightness of Boshan. During the Dade reign (1297-1307), Cao Zhibai served as Instructor at Kunshan. However, soon afterwards he resigned and went into reclusion; he was a figure who maintained relations with scholars from different ethnic backgrounds.

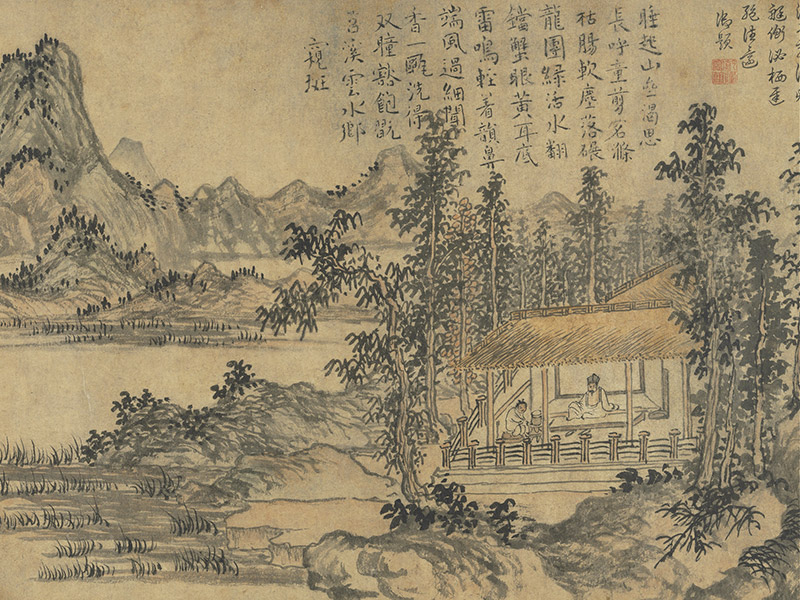

Landscape

- Cao Zhibai (1272-1355), Yuan dynasty

- Album leaf, ink on paper, 68.1 x 34.3 cm

This painting depicts landscape elements divided by a stretch of water, the mountains rendered in ink and appearing almost dripping wet. In the foreground are two pines that rise upwards, the brushwork and forms deriving from the style associated with the Li-Guo tradition of the Northern Song period. Scorched ink was added to highlight the main elements, creating a new and interesting interpretation in ink of the Li-Guo manner during the Yuan dynasty.

Scroll Brocade of Collected Yuan Paintings

- Various artists, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Handscroll, ink (and [light] colors) on paper, 23-27 x 61.5-113.7 cm

The eight paintings include those by Zhao Mengfu, Guan Daosheng, Ni Zan, Wu Zhen, Ma Wan, Zhao Yuan, Lin Juan'a, and Zhuang Lin. Despite the difference in their periods of activity and the varied subjects, the scroll is a masterful collection of landscape and bamboo-and-rock paintings from the Yuan dynasty. For this exhibit, the front half is on display for the first rotation, including the works by Zhao Mengfu, Guan Daosheng, Ni Zan, and Wu Zhen, followed in the second with those by Ma Wan, Zhao Yuan, Lin Juan'a, and Zhuang Lin.

Four Paragons of Filial Piety

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Handscroll, ink and colors on silk, 38.9 x 502.7 cm

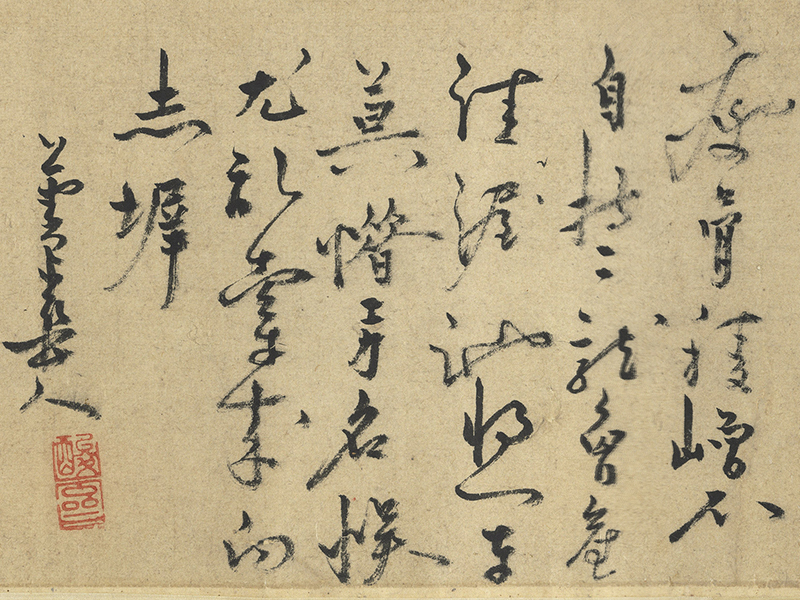

Colophon to "Two Horses"

- Guan Yunshi (1286-1324), Yuan dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 19 x 81.5 cm

This work was written in cursive script, the forms tending towards slenderness but strong and with a loose structure. The soft and rounded strokes also have a vigorous and direct manner. The lifting of the brush exhibits quick flicking, the force mostly rapid and moving. The work as a whole has unusual form and dynamism. This style with its unbridled bravura contrasts with the meticulous beauty of strokes and characters practiced in the calligraphy of Zhao Mengfu, an elder contemporary of Guan Yunshi.

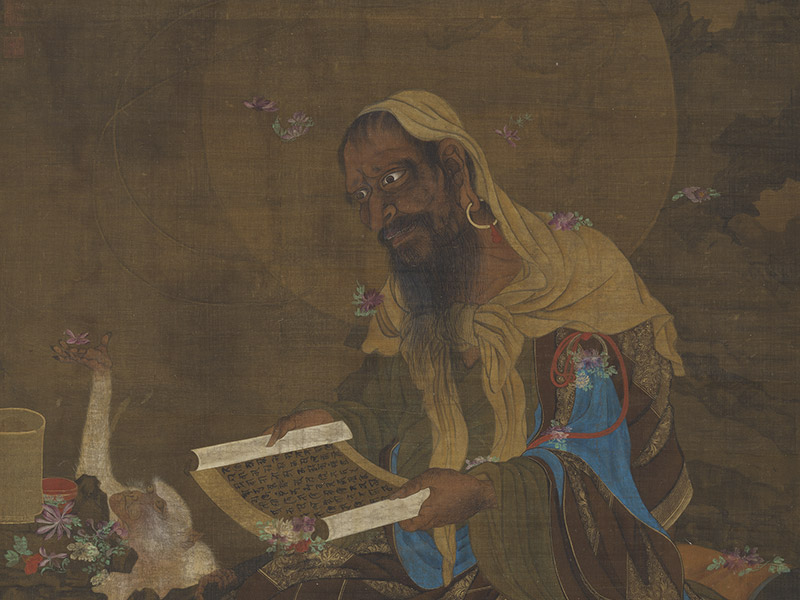

Heavenly Petals Falling on an Indian Monk

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 175.3 x 98.2 cm

The artist depicted the drapery folds of the figure with rounded and turning lines that are strong and powerful nonetheless. The different textures used for the decorative clothing, falling petals, and white monkey are all meticulously rendered. The background landscape enveloped in clouds and mists is portrayed in monochrome ink, while the clothes and flowers are painted with bright colors, creating for a strong contrast. This work bears neither seal nor signature of the artist, but the style of the figure accords with the tradition of lohan figures painted as foreign-looking monks in the Yuan dynasty.

Ratnasaṃbhava

- Anonymous, attributed as Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, silk tapestry, 84.6 x 57.1 cm

The scroll depicts Ratnasaṃbhava, the Buddha of the South for one of the cardinal directions. The figure's right hand is in the "bestowing" gesture (mudra), while the left hand holds onto the robe in the "wish-granting" mudra. The body of this buddha is golden yellow and appears upon a Treasure Horse, the deity shown seated on a lotus pedestal. On both sides of the body halo are six auspicious accompanying creatures: the elephant, flying horse, makara, naga, and garuda. These, however, are motifs related more to depictions from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Image for the New Year

- Anonymous, attributed as Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, embroidered silk gauze , 216.6 x 63.8 cm

The scroll here depicts a child wearing Mongolian clothing and riding on a goat as he looks back. Two other children and eight other goats create a group for "Nine Goats (Yang) for the New Year," an auspicious subject in traditional China. The composition is similar to that of "Welcoming Spring," a textile in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The forms of the various plants are beautiful and the embroidery technique extraordinary, making this an excellent example of textile art from the Yuan to Ming period and perhaps related to achievements in imperial weaving in the Mongol Yuan period.

Shri Hevajra

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Hanging scroll, silk tapestry, 86.3 x 63.4 cm

This work was probably at first a rectangular thangka, a traditional form of Tibetan hanging scroll; perhaps, due to damage, it was remounted after entering the Qing court collection into its present Chinese-style scroll format. Starting in the Southern Song period, Tibet and the Western Xia ordered Buddhist images in embroidered tapestry from such places in China as Hangzhou. The simple and straightforward style of this tapestry and the form of the halo are similar to those seen in Buddhist prints from the late Yuan dynasty. Although this image of Shri Hevajra may be based on a Tibetan model, it does not show the female dākinī, suggesting the influence of Chinese culture. For this reason, it may be a product of Chinese craftsmanship from the fourteenth century.

Thangka of the Taklung Monastery Abbot Tashi Pal

- Anonymous, Tibetan, 13th century

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on cloth, 50 x 38 cm

The painting, damaged in many places, had been frequently repaired. On the back is text written in Tibetan that suggests the scroll was done around the late thirteenth century. The composition of the painting follows the formula of a high guru depicted on a tall canopied pedetal with railings and accompanied by bodhisattvas and guardian figures below. Such an arrangement reflects the importance attached to guru devotion and temple lineage in Tibetan Buddhism.